Why we need to maintain a healthy shoulder joint

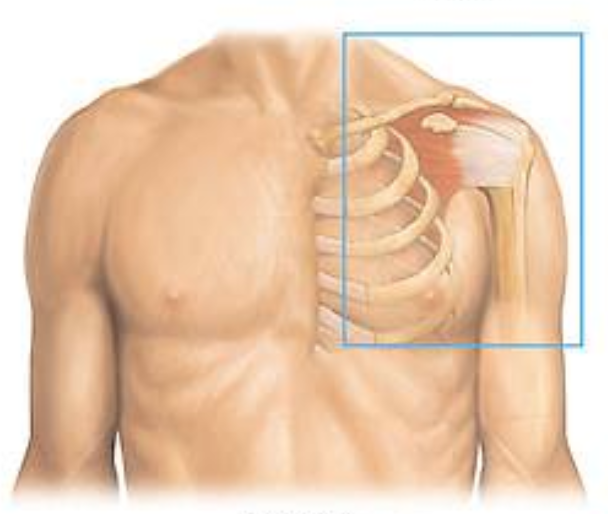

This week we kicked off our new Saturday Club sessions with a special interactive workshop on the body’s most flexible yet vulnerable joint – the shoulder. You may not know that the shoulder girdle is made up of a set of intricate bones and muscles that all work together to form a joint which is more mobile, and has a greater range of motion, than any other part of the body. However, the fact that the shoulder joint is so complex means it can also be more be prone to injury if we don’t look after it properly.

Let’s begin by taking a closer look at the shoulder complex. It focuses on four main joints: the glenohumeral (ball-and-socket) joint, which is the main mover of the shoulder; the sternoclavicular joint, which is the main mover of the scapula (shoulder blade) in protraction, retraction, depression, elevation and rotation; the acromioclavicular joint, which is more of a passive joint; and the scapulothoracic joint, which serves a similar purpose to the sternoclavicular joint above. On a daily basis, we use a combination of these to help the shoulder perform various ‘rotating’ movements in the sagittal plane (a hypothetical line perpendicular to the ground, dividing the body into left and right), giving us a freedom of movement that we often take for granted.

Gliding, or rotation movements, can include adduction (lowering the arm sideways from a raised position down towards the body); abduction (raising the arm sideways from a lowered position up away from the body); flexion (raising the arm up at right angles in front of the body); extension (pulling the arm backwards behind the body); internal and external rotation (positioning the forearm at right angles to the upper arm, and then bringing it inward towards the body, and outwards away from the body, respectively); and circumduction (using the full range of shoulder motion by circulating the entire arm around the joint, clockwise or anti-clockwise).

As you can soon see if you’re attempting any of these movements, understanding how the different components work together, and how to maintain complete flexibility, is paramount to help prevent tension or pain, especially as we get older. For example, a common reason the shoulder is prone to injury is because many of us don’t realise that scapula is part of the joint, too. In abduction or inflexion movements, you’ll find there’s a small bone called the acromioclavicular (highest part of the collar bone), that cannot physically “allow” the humerus to move beyond 90 degrees, so at this point, you rely on the scapula to rotate in order to complete the movement. However, scapular rotation becomes difficult if the shoulder blade or surrounding muscles are tight, which can then progress into a chronic problem, especially from the mid-40s onwards, if the muscles are not mobilised in the right way.

So now let’s take a look at some of the most common conditions that can occur if we don’t look after our shoulders properly (some of which can progress without us even realising), and what we can do to alleviate symptoms, or prevent them from developing in the first place.

Frozen shoulder

Also known as adhesive capsulitis, frozen shoulder is a condition where the entire shoulder joint can seize up due to a tightness or swelling of the shoulder joint capsule. The capsule – which is the deepest layer of soft tissue surrounding the shoulder and plays a pivotal role in keeping the arm bone within the shoulder socket – actually thickens and contracts, losing its ability to stretch. Frozen shoulder is usually detected by muscle spasms, and although there is still a great deal to learn about the condition, it is thought to be brought on by a number of factors including inflammation, or immobilisation due to injury, surgery or illness. However, it can also occur as a result of heart attack or stroke.

Frozen shoulder occurs in around 2% to 5% of the population, especially between the age of 40 and 60, and can leave muscles feeling painful and stiff, with loss of normal range of motion, for months on end – even years if left untreated. There are medications that can help, such as painkillers, steroid injections and saltwater solutions to soften the lining of the capsule.

Rotator cuff injuries

The rotator cuff refers to a group of muscles and tendons which surround the main mover of the shoulder joint (i.e. the glenohumeral joint), and ensures that the humerus (armbone) sits safely in the glenoid fossa (a shallow depression in the scapula, in which the head of the humerus fits), especially during movement of the joint.

Often confused with frozen shoulder, rotator cuff injuries occur when the muscles become torn or impinged (i.e. either inflamed or pinched, resulting in swelling). Rotator cuff tears or impingements make it difficult to raise the arm above 90 degrees and can be caused by a sudden trauma, such as a fall, or from lifting heavy items. Alternatively, injuries can develop slowly after months or even years of wear and tear, which is known as repeated microtrauma.

The good news is that as with most muscles in the body, apart from getting lots of rest, Pilates can be used as an effective rehabilitative exercise before resorting to medication – although you may also need painkillers or steroid injections. It’s really important to mobilise the shoulder, so in terms of exercise, making small changes to movement patterns, re-learning how the shoulder blade moves while you are doing a particular exercise, and even considering the posture of your thoracic spine, can do a world of good when recovering from a rotator cuff injury.

There are several exercises that help to mobilise the shoulder joint, as featured in our Shoulder Girdle workshop. If you’d like to find out more, contact Bea at beatrix@mytimepilates.co.uk.

Our next Saturday Club session will focus on the Hip Joint, so stay tuned for more details or book your space today by emailing: sarahoffice@mytimepilates.co.uk.